Playing in the outdoors can make life more colorful. Illustration by Gretchen Leggitt.

Playing in the outdoors can make life more colorful. Illustration by Gretchen Leggitt.

Kirkwood’s Chair 6 whisked a group of teenage boys to the top of the Sierra Crest. The kids sitting on the chair were from some of California’s roughest neighborhoods in cities like Sacramento, Bakersfield, and Watsonville. Between them, they represented much of the diversity of a place like California: white, black, H

One of the teens, James, had had a particularly rough go of it, having fallen into hard drug use and theft following severe abuse as a child, but he was about to discover something that would give him peace, if only for a day. It had snowed a foot the night before, and these kids were about to see what snowboarding in deep powder can do for a person’s outlook on life.

Kirkwood is full of stashes, so James and the other guys had no trouble finding one of these hidden spots. Pulling through a thicket of dense pine, the boys moved apprehensively, not sure about their run selection. Then the trees opened up, and everything clicked into place. Below them, an untouched field of fluffy powder beckoned.

They ripped through the glade, letting out whoops and hollers, high and euphoric on a drug they hadn’t known existed. Time melted away along with their problems, and they choked on the clouds of ecstasy together.

A few short minutes later, panting at the bottom of Chair 6, they wore grins hidden beneath the snow caked on their faces.

They looked back as the rest of the boys slowly streamed out of the trees. The last to emerge was James—and he had changed.

The boy who had entered that tree run was angry and bitter, deeply upset with the world, impressed by nothing. The person who emerged from those pines was full of a lightness and an elusive peace. His smile was radiant and

Eric Rhea finds his bliss during a Black Ski Summit in Niseko, Japan. Eric Rhea photo.

Eric Rhea finds his bliss during a Black Ski Summit in Niseko, Japan. Eric Rhea photo.

A few years back, I was fortunate enough to lead a group of at-risk group home kids on excursions such as this.

During those experiences, I often wondered what being in the mountains—away from violence, crime, and the history of their troubled youths—would do for them in the long run.

I don’t claim to know what is best for people. Everyone has their own experiences, and what benefits someone in life is almost always subjective. But I’ve witnessed the transcendental and transformative power that the mountains can play in young people’s lives. I’ve seen a powder grin shine through burden and pain.

Given how powerful riding powder can be for almost anyone who experiences it, I've always been surprised that a more diverse population hasn't taken to it.

But should all minorities aspire to be like white people and do the sports white people like? No. But people in an equal society should have the ability to make a choice, and to seize the breadth of opportunities that the world presents. Not cultural hegemony; just cultural healing.

If one thing is for certain, it’s that affluent white people don’t hold a monopoly on the enjoyment of sports. Many of the best athletes in the world are black men and women. The pursuit of, and passion for, sport is universal. In our society, we’re all used to seeing black people crush it on the court and field, but for many reasons, black athletes, amateur or professional, are not, for the most part, to be found in the mountains.

According to a SnowSports Industries America study, in 2013, black people made up just 7.3% of alpine skiers, while 72% were caucasian. In terms of snowboarding during that same year, African Americans were a bigger piece of the pie at 10.2%, but white people still made up the lion's share.

These days, not a season goes by that I don’t ask myself why. Sure, the usual suspects–the white and privileged–are to be found in every river eddy, smoke shack, and campsite imaginable, but where is everyone else?

At least a few times each winter, usually on a chairlift, some friend or skier will turn to me, and acknowledge the big elephant on the hill.

“Where are all the black people?”

“Why don’t black people like to ski?”

“How come minorities don’t like the outdoors?”

More often than not, these conversations end as quickly and unproductively as they start. Someone will contribute an incredibly vague catch-all (“black people don’t like the cold”), and the chance for a productive conversation dies right there on the lift.

As easy as it is to generalize the reasons for the lack of minority groups participating in snow sports, the actual factors behind this phenomenon are nuanced and specific, and to someone who’s paying attention, not all that surprising.

To find out the answers to these questions, I sat down with several well-known and respected members of the African American skiing and snowboarding community. As is the case almost always in life, these guys don’t speak for everyone, but they do have unique viewpoints that shed light on a rarely discussed issue.

Old friends Marvin Howard and TGR co-founder Todd Jones catch up and scheme new adventures. Marvin Howard photo.

Old friends Marvin Howard and TGR co-founder Todd Jones catch up and scheme new adventures. Marvin Howard photo.

For starters, I interviewed Jackson Hole local legend Marvin Howard, a member of the Jackson Hole Air Force and a badass townie ripper of more than 20 years. Growing up, Marvin had a supportive family that encouraged him to try new things. Over the years, he’s thrived in Jackson by owning and managing his own moving business, Mountain Movers. He is a passionate and dedicated ski bum and is well acquainted with the mountain lifestyle.

I also connected with Eric Rhea of the National Brotherhood of Skiers, an organization that has been tirelessly encouraging African Americans to get out on the snow for over 40 years. A self-made man who works as a successful antique dealer in New York City, Eric is unique in that he lives at the confluence of poverty, inequality, and obscene wealth in contemporary Manhattan. Eric is active in many youth initiatives as well as being a key player at NBS ski summits around the world.

Eric’s brother John also sat in on our interview and contributed to the conversation. A Harvard-educated real estate developer, John Rhea is brilliant. As a father, John has seen the way our country makes it harder for his kids, and this unique viewpoint of fatherhood has enabled him to play a sage-like role on this topic.

The Rheas see it from 35,000 feet, and Marvin sees it when he walks out his front door, but both angles yield a disturbing understanding of the past, and a hopeful view toward the future.

Economic Uncertainty

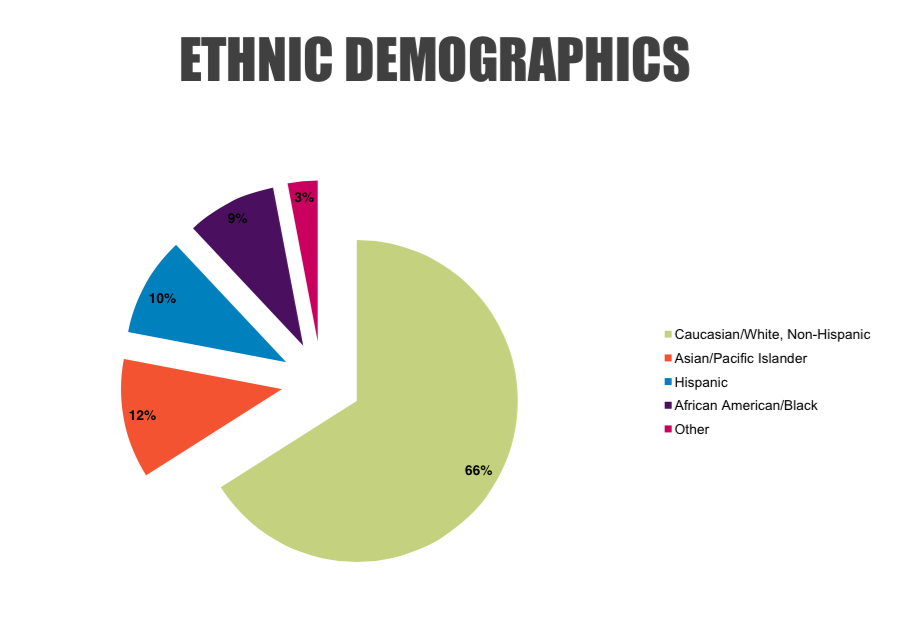

This pie chart comes from a 2012-13 Snowsports Industry of America participant study, and shows the ethnic breakdown of snowsports participants in the US. SIA graphic.

This pie chart comes from a 2012-13 Snowsports Industry of America participant study, and shows the ethnic breakdown of snowsports participants in the US. SIA graphic.

This conversation begins with money and what it does to human priorities. Growing up in a world of middle-class affluence and comfort leads people to make decisions differently than those from less well-to-do circumstances.

Let’s face it: snow sports are expensive. Just getting to a ski area can cost a lot of money, and the sport can be put entirely out of reach if you don’t own a car. But even once you’re in the mountains, there’s food, lodging, equipment and overpriced lift tickets, and that’s not even including your extracurricular nocturnal activities.

On the flip side, maybe you’ve committed to living in the mountains, as many ski bums and dirtbags have throughout the ages. This means, assuming you’re a 20 or 30-something, that you’ve put your future on hold so that you can live the dream in the prime of your youth—and decades before more responsible friends retire to do the same. However, a 10-year binge as a ski bum can often yield a nasty hangover, and what was for a brief time desirable and fun at 21 is now immature and irresponsible at 31. Trust me, I know.

For many Caucasian people, this break from reality is the acceptable cost of living the good life, because most white folks know that there’s a dependable on-ramp back to a professional career after they’ve had their fill of the mountain lifestyle.

Due to systemic inequality in the United States, such on-ramps often don’t exist for young men and women of color. The decision to dedicate a significant chunk of your early adult life to play in the mountains is perceived as irresponsible. The pressure to steer toward a conventional path of stability is often self-imposed as well as reinforced by one’s immediate family, who understand how rarely opportunity knocks.

“It’s obvious that if you’re a minority in the United States, you have to work harder to get ahead–way harder,” Eric explained. “Even once you get your education, just to compete for jobs and resources… the thought process is, ‘I must be an idiot to think I’m going to go play in the snow for ten years.’”

Piggybacking on his brother’s statement, John also pointed out that a lot of pressure for mature decision making comes from the immediate family. “Most people try to steer their children toward economic certainty,” he said. “This is about pathways and careers that people have seen work in the past. The average low-income family hasn’t seen ski-bumming lead to economic stability, if they’ve been exposed to it at all. They see it as wasted youth.”

Most people try to steer their children toward economic certainty,” he said. “This is about pathways and careers that people have seen work in the past. The average low-income family hasn’t seen ski-bumming lead to economic stability, if they’ve been exposed to it at all. They see it as wasted youth.

You hear a lot buzz about young people taking gap years, of traveling and seeing the world, sowing their wild oats and living life to the fullest. For those in a position to grow from such experiences, they can be immensely valuable. But that value only comes if there is a light at the end of the tunnel—some assurance that even if you put your professional life on hold, there is an opportunity to pick back up where you left off when you're ready to get back in the game. This re-entry into a traditional career path can be a challenge for anyone, but for those whom our society has put at an enormous economic and social disadvantage, it can prove to be an impossible hole to dig out from.

In a world with very few chances for upward mobility, the thought of missing that window, of throwing your future under the bus for the sake of the instant gratification of a season or two of face shots is for most young people just too big of a chance to take.

Another factor is the idea of social autonomy, or not having a financial responsibility to one’s family. In many impoverished and developing nations, families band together. In urban areas where there is a greater concentration of poverty, this is also true. Families are more likely to stay together to pool funds and resources.

“If you’re from a middle-class family, a wealthy family, it’s really about you,” John continued. “Your family wants what’s right and best for you, including having those life experiences. But if you come from a family where means are tight, you have to provide and help the nuclear unit, so those choices don’t become individual; they remain communal.”

History and Fear

Minority populations are held back from skiing and snowboarding by geography as well. Like most migrant populations throughout history, as African American people settled into communities during the 19th and 20th centuries, they tended to put down roots around other people of similar races and social status. This led to many cities having concentrated populations of African Americans and other minorities. These migrations along racial lines meant that the cities of America were diverse and multicultural, with many different types of European and African ancestries represented. It also meant that the open spaces of the Western U.S. were mostly left to white people to settle.

It may seem like common sense, but most of the regions that have great access to outdoor recreation in this country are heavily rural: the Northern Rockies (Montana, Idaho and Wyoming) are a prime example of this trend in population distribution. Of the Intermountain West, Denver and Salt Lake City are the only two major metropolitan areas that offer reasonable access to mountain sports. Denver, in particular, has a large minority population, but thus far, widespread minority recreation in the I-70 corridor has not happened, although things are changing.

Part of the geography problem is that committing to living in a ski town, to being a ski bum, is just that: a total commitment. For those intrepid, dumb or wise enough to see through the rat race of life, this commitment can be an enormously rewarding experience. But if you’re not all in, the economic feasibility of skiing and snowboarding becomes further and further out of reach.

To participate, either you’re poor and you live and hustle in a mountain town or you’re rich and you can play wherever you want. This dynamic creates a very black and white choice for most young people of color.

“In mountain towns, you have people who are ski bums—they are hard working, basic wage people a lot of times. They work in the restaurants, other low wage jobs, but because they live right there, they have access,” Eric told me. “It’s a location thing. It’s a recreation thing, like, ‘This is what I do. I need to get out and have some peace of mind at the end of the day.’ So for the ski bum, it’s an easy thing because there’s no need to travel. But people who live in city centers or urban areas, we gotta actually hop on a plane, book a hotel, pay a hundred bucks a day for a lift ticket.”

Marvin also felt that geography plays a big role, however, he asserted that Americans in general lag behind other cultures in terms of encouraging young people to travel and experience new things.

Europeans, Australians and New Zealanders go do that [travel] no matter what color, race or creed. So, it’s not race, it’s not color, it’s a uniquely African American situation.

“Europeans, Australians and New Zealanders go do that [travel] no matter what color, race or creed. So, it’s not race, it’s not color, it’s a uniquely African American situation,” Marvin iterated. “I meet African people from Africa, and they are told to get out of Africa and travel. The average person in Europe gets their passport when they’re eight to ten years old—here, the average American doesn’t even have a passport.”

Marvin touches on an important facet of this conversation when he mentions that in other places, people with dark skin aren’t held back as they are in America. His argument highlights that overall, Americans are heavily risk-averse people. Parents in this country, for the most part regardless of their financial status, discourage travel and what most would deem unsure outcomes.

Perception

The Rivers family readies for a day on the hill. The kids' expressions cover the spectrum from mischievousness, boredom, and apprehension—but Mom and Dad are stoked! (from left to right): Henri D.L. Rivers IV, Henri D. Rivers, Helaina D. Rivers, Karen A. Rivers and Henniyah D. Rivers. NBS photo.

The Rivers family readies for a day on the hill. The kids' expressions cover the spectrum from mischievousness, boredom, and apprehension—but Mom and Dad are stoked! (from left to right): Henri D.L. Rivers IV, Henri D. Rivers, Helaina D. Rivers, Karen A. Rivers and Henniyah D. Rivers. NBS photo.

Something that I noticed during my time as a teacher and youth advocate was that the kids like James, even well into their teens, always loved snow sports, but still maintained a belief that these activities were part of a system that wasn’t meant for them. This was fascinating because it showed me how perception created boundaries for these kids and others.

For a long time, skiing, golfing and other like sports were mostly for white people. Therefore, the assumptions that people of color weren’t welcome were based on more than just what they’d seen on TV, or in their neighborhood—they were based on the slow grind of exclusion, poverty and injustice that they’d both participated in and been the victims of.

The Rhea brothers, both exposed to skiing when they were little kids, learned firsthand how a person’s identity is actively shaped by experience. If you keep a child in an urban setting for their whole youth, they won’t have a chance to identify with the outdoors.

“If someone labels something as a ‘white’ or ‘black,’ that’s because they’ve gone through a significant portion of their life and they start to define things with much more rigid definitions,” John reinforced. “If you expose a young African American or Latino kid to snowboarding in the mountains, they won’t define it as ‘white,’ they’ll define it as a part of ‘me.’ But when you grow up without that experience, and now you’re 15, 18, 25, your perceptions are much more cemented.”

Eric stressed that he’s watched the transformative effect that the National Brotherhood of Skiers and programs like Hoods to Woods can have on young minorities. But you have to plant the seeds early enough, otherwise skiing and snowboarding are perceived as a novelty, and not something that is actually attainable.

We take inner-city kids from the housing projects in NYC. We take them out snowboarding; it’s a mentorship program,” Eric recounted. “Three of the kids left to go to college this year in Colorado literally because they love snowboarding so much. Nobody from their families had ever gone to college, but the motivation for them now is, ‘I need to study, and do well, in order to be able to afford to do this, because I love this now!'

However, sometimes the passion and love derived from skiing and snowboarding can actually inspire a person to lift themselves out of adversity. When you take a child out of their circumstances and expose them to something new, it opens up an entire world of possibilities. In his life, Eric has also witnessed this transformative power of snow sports.

“We take inner-city kids from the housing projects in NYC. We take them out snowboarding; it’s a mentorship program,” he recounted. “Three of the kids left to go to college this year in Colorado, literally because they love snowboarding so much. Nobody from their families had ever gone to college, but the motivation for them now is, ‘I need to study, and do well, in order to be able to afford to do this, because I love this now!’”

Contemporary Urban Culture

Eric and an NBS crew take a moment of reprieve from the deep pow at Niseko, Japan. Eric Rhea photo.

Eric and an NBS crew take a moment of reprieve from the deep pow at Niseko, Japan. Eric Rhea photo.

I asked if when the Rheas shared their life story, and their success and the unique ways they enjoy it with younger, poorer minority mentorees, they were seen as sell-outs. To the contrary, the type of success and affluence that they possess is one of urban culture’s highest ideals. Not something to shun, but something to attain and work toward.

“We’re in an environment today where there’s a lot of glorification of what I would call 'excessive lifestyles,'” John explained as he took me to school. “So whether that’s having a yacht, or having a ski chalet, most African Americans see that as aspirational,” he continued. “I don’t think the youth sees it as selling out. But they want to do it in their own cultural way. They don’t want to go out and do it the way it’s been perceived historically, they wanna go with their crew and do it in a way that they see as culturally authentic.” Eric's own rap anthem below reflects that desire:

So for a lot of young men and women of color, it’s not the act of skiing or riding that is desirable, but the ability to afford to do so that is inspiring. The ski and snowboard lifestyle is, in a lot of ways, an excessive lifestyle, making it a status symbol in our society.

It’s pretty clear that ski bumming doesn’t fit into this aspirational image of excess, but how the Rheas go snowboarding–showcasing their freedom and success on expensive snowboarding trips to the mountains of Japan, Chile and the Northern Rockies–is deeply inspiring to those in the urban mindset.

On this thread, when discussing his rap video, Eric explained that to the common urban kid, “This [snowboarding] is balling on a whole ‘nother level. I knew the psychology behind someone watching the video and saying ‘This is some fly, next-level shit that I never understood was out there.’ Then it sets up this whole new mindset of ‘I think I want to experience this.’"

A More Diverse Future?

Marvin emerging from the white room at Grand Targhee. If more people of all cultures could have experiences like this, the world just might be a better place. Marvin Howard photo.

Marvin emerging from the white room at Grand Targhee. If more people of all cultures could have experiences like this, the world just might be a better place. Marvin Howard photo.

Certain parts of the American culture and economic system have limited many people’s access to the mountains. Because snow sports are expensive, there will always be those who just flat-out can’t afford to do them, but as a society, people should do more to welcome minorities into the mountains, and at the same time not project caucasian cultural narratives onto that experience.

People who practice outdoor sports, and the incredible flow state they produce, have tapped into something that overcomes the divides our culture creates along the lines of skin color, religion, or political preference. As humans, the ecstasy that comes with a powder turn or a hike on a long-forgotten trail should be available to everyone. If everyone was out taking pow turns, or finding their bliss in some other way in the natural world, our society would most likely be a much happier, better place.

But things are changing. With passionate players such as Marvin and the Rhea brothers bringing young people into the fold and setting a precedent, acting as mentors and planting seeds that will in time bear fruit, the mountains will grow more diverse.

According to the SIA study, African American participation in snow sports actually shot up dramatically between 2009-2013. In 2009, African American participation in alpine skiing was at just 2% of skiers, but only five years later, that number had grown to 7%. During the same time, African American participation in snowboarding grew even faster, going from 3% in 2009 to 10% in 2013.

Marvin, himself a life long emissary of stoke, understands that the divide that prevents some from skiing and riding is not genetic, but cultural. “Anyone who dedicates their life and dedicates their mindset to it can and will be a good skier,” he told me. “It’s not about race, color or creed–it’s about dedication to the lifestyle and to the sport.”

ai2caad

May 28th, 2015

I’ll share my comment, being black. If you really want to reach the African-American demographic, hispanic, etc you got to reach them where they are. Hit up the South East and share the good news gospel on what life is like the west. Have Jeremy Jones hit up some black schools in Orlando, Florida. Some of these kids, like me, (when I was a kid) never know anything outside the block they grow up on. And the black schools don’t really help much either.

There are a few factors to consider. Outdoor sports for blacks is in the sun, running, basketball, baseball, and football. Even though blacks move away to the west, and midwest, a lot of our roots is the Southeast. Black schools in the southeast have a lot to do with that because of limited sports programs. Historically most of these schools have a great basketball and football programs. Hence the reason why Florida has produced the most draft picks NFL/NBA for many years.

A lot of kids in the southeast don’t have fathers, so single mothers will prefer they play basketball or football to have a father figure in their life. Learn some discipline. Money is tight, and they can’t afford college, so playing basketball or football has promises of a financial future and job security. Read the story of Allen Iverson. Many blacks in the southeast live that story.

It would be nice to live in the North west, but those blacks who do live out west like Seattle, WA, or Oregon are very privileged and migrated there because of the military, and started there families there, and the sports that there kids get involved in would be vastly different from the south east. A black kid growing up in Portland, OR will most likely be exposed to snowboarding, rock-climbing, and skiing, etc.

The key to breaking down walls and bringing diversity to every outdoor sport, not just limited to skiing, but all other sports limited in diversity. Climbing, mountain biking, etc is exposure. TGR could show films in Mississippi, Louisiana, Missouri, Florida, Georgia. Getting out into the trenches of these urban minority communities then and get involved. Of course it’s a lot of work, but the pay-off is even greater. Start a NOLS branch in Georiga or something.

Ryan Dunfee

May 28th, 2015

Hey AL2CAAD, thanks so much for your thoughtful comment. I think your idea for a Southeast tour is a great one. We do do regular movie premieres in Atlanta, Florida, Virginia, North Carolina, Louisiana, Missouri, and Texas almost every fall, but it’d be great opportunity on those trips to see if we can get the athletes on the tour to tour some of the schools nearby and tell the students what they do.

TABthewriter

May 28th, 2015

Thanks, Sam- this was a thoughtful and timely piece.

I remember when I was younger, in addition to wondering why there weren’t more black people skiing and snowboarding, I often wondered why there weren’t more black people in Vancouver o/a the Canadian west.

There were a few exceptions (Joe Forte became a legend in Vancouver, as did Wellington Delaney Moses in Barkerville), but by and large there was never a groundswell in terms of a black community in this part of Canada- Most people that escaped/moved/immigrated north of the border during and following the civil war settled in the Maritimes (Africville) or Ontario, most black communities nowadays found in larger urban centers (as is the case in the ‘states).

There are definitely more black people that have relocated to Canada in the past fifty years, certainly in Vancouver, too, but my impression is that few are African-American (moving from the ‘States) but have instead arrived as first generation immigrants from jamaica, Haiti, Somalia and other locations.

It has always kind of perplexed me that more African-Americans did not or have not relocated to Canada…

I’m not so daft as to suggest we have some kind of Utopia going up here (racism is alive and well) but given Americans’ propensity for saying stuff like, “If it gets any worse here, I’m moving to Canada,” it’s kind of surprising more people don’t.

Not to detract from the thrust of the piece at all (Black Turns DO Matter), but one demographic that suffers crazy amounts of systemic marginalization and racism in Canada is our First Nations population, what you might refer to as “American-Indians.”

While the USA practiced more of an active eradication policy with regards to many First Nations groups, the tactics employed in Canada were (are?) more along the lines of isolate and assimilate- Our residential school abuse scandals, inferior housing for those on reserves, lack of medical services and access to clean drinking water for many in these communities has been criminal.

While many First Nations people today find themselves living in inner cities, many more live in rural areas where opportunities to recreate in the mountains are available- With some guidance, political will and assistance.

Similar in its mandate to the NBS, I’d recommend checking out the First Nation Snowboard Team- http://www.fnriders.com/#!contact/c1lmq

While it’s not precisely the same hurdles faced by black youth, there may be some good opportunities to share success stories in order to advance the availability of these sports to people of all colors and creeds.

And where groups like the FNST are concerned, it would be great to see its scope expand to include other parts of the U.S besides just Washington State…

SHREDFNDN

May 29th, 2015

A tip of my hat to Sam for delving into this issue. It is one that has been discussed amongst friends but also within in an industry that is forced each season to contemplate ways to remain sustainable.

Like Sam, I too have witnessed the magic of bringing kids up to the mountains. For close to ten years I have worked in the snowboard youth development field as a member of the national staff for Burton’s Chill Foundation, as Senior Program Manager for Stoked Mentoring and as Program Director and Advisory Board Member for the Hoods to Woods Foundation mentioned in this article. I have also, just this past year established my own foundation to expose more youth to snowboarding in upstate New York. One could argue that this is my way of living the snow bum life, but it stems from the fact that in over 20 years of youth development work, I have never seen anything have the transformative effects upon youth the way snowboarding does. But as a snowboarder who is also black, I found myself often saying; “yeah, but” when going through this article. With that being said, I am commenting as a snowboarder and only speaking from my experiences from this view point.

I understand that the nature of the article was to start a conversation and, as that, I agreed with a majority of what was said and written. However, Sam initiates this conversation by stating that there are generalizations the come about when discussion this topic and unfortunately I felt that some of these ended up making their way into the article. In the years that I had to go out and promote the programs that I worked for, I never suffered from a lack of black and brown youth wanting to go snowboarding. In fact, as an educator, when I mention the fact that I snowboard and that I have taught kids how to snowboard, the first question that I get is “CAN YOU TEACH ME!” When the same demographic of kids see me with my snowboard, the level of interest and questions are the same. So I say this to dispel some of the notion that these kids see this as something antithetical to “black authenticity.” Now, could this be different when talking about skiing? I don’t have the answer to that.

As Sam and as many comments have mentioned, what is lacking is access and affordability. While we are talking about places such as Jackson, Hokkaido, Utah and such, the fact of the matter is that where I am sitting here in the Hudson Valley of New York State, we have at least four cities with a considerable communities of color that lie within less than an hour and a half from at least half a dozen ski areas. Honestly, I could go on and on about potential ways to address the access and affordability reality (and, to be honest, this same issue faces poor whites in rural communities as well).

I don’t say any of this to take away from the purpose of Sam’s article nor do I discount the opinions of the individuals that he interviewed. I have met Eric in the past. He is a passionate guy in this regard and he rips. Yes, there are definitely some structural hurdles that have, historically, contributed to a lack of participation. However, to take to 35,000 foot view and not to see how, specifically, the snowboard community that at its core values individuality which, in turn, organically brings forth diversity is to (in my opinion) do a disservice to the nuance in which he seeks.

Thanks for publishing this article and I look forward to seeing where this conversation goes in the future.

Danny Hairston

Founder/Executive Director

SHRED Foundation

Nicholas Backlinks

March 6th, 2020

So that’s the reason. Very cool article, I have read it all. Thanks for sharing this great info.

Roadside assistance

Andrea J

November 14th, 2021

Very interesting reasoning behind all of this. I also agree, it was very well explained and no need for me to read it all, this comment helped alot. Thanks.

AJ. https://www.treeremovalmchenry.com/

Brian Hyde

August 29th, 2020

I grew up in a ski industry family; my stepdad was a racer turned coach/teacher turned ski area manager and my mother was an instructor. Living in Montreal until 12, I also learned to skate and play hockey.

At about age 55, I was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. I have given a good bit of thought to the following questions, particularly in the last few years, “Why are most of the people in my Parkinson’s exercise and dance classes and in my Parkinson’s book club white like me? I benefit a lot from those therapeutic activities, so why wouldn’t people of other colors and other backgrounds who also have Parkinson’s disease benefit from those same classes?” (Understand that taking care of yourself with Parkinson’s takes up a whole lot of your time and energy, but, it also give you lots of time for “pondering”.)

In watching this year’s National Hockey League playoffs, in the Black Lives Matter context of 2020, it came to me that the reasons that snow sports and ice sports look so white very likely are similar to the reasons that my Parkinson’s therapeutic activities look so white.

If more youth of color were offered meaningful opportunities to ski (downhill and/or cross-country) and/or skate (maybe just for skating’s own value, or maybe for figure skating, speed skating, or hockey), perhaps a few adult members those youth’s families who have Parkinson’s or who know other people of color who have Parkinson’s can be provided with opportunities to learn about Parkinson’s therapeutic classes.

Here is how I connect winter sports and Parkinson’s therapy classes in my own head (and in my heart, to be honest). I want to ski and I want to skate. At 71, with 18+ years of Parkinson’s progressively trying to destroy the ability of my neurological system to communicate properly, skiing and/or skating are difficult and dangerous. The only way I can even try to do what I want to do is to work really hard in those therapeutic classes, slowly re-building balance, flexibility, strength, and dexterity. All of those systems are diminished by Parkinson’s Disease. In every class my underlying motivation in working hard is to ski, skate or hike. It’s that simple.

Thank you for what you wrote. I can’t imagine having grown up without having opportunities to ski or skate (or just to wander in and camp in the mountains). Now, not because of my race or my cultural background or my ZIP code, my access is restricted. I want to reclaim just a bit of those experiences. Whether I am currently OK with the concept of acceptance or not, I can only make a productive effort to reclaim snow and ice by accepting some of my Parkinson’s limitations as actual limitations and by learning how to get past others of those limitations through hard work (and exceptional teachers and coaches).

I live in Denver and would like to do whatever I can to help remove some of the barriers to accessing snow, ice, mountains and Parkinson’s therapy in Colorado and beyond,

Brian Hyde