TGR Tested: Rocky Mountain Slayer C90 29

Popular Stories

Is the Rocky Mountain Slayer more than just a downhill bike in disguise? Max Ritter photo.

Is the Rocky Mountain Slayer more than just a downhill bike in disguise? Max Ritter photo.

What’s more fun? A bike that has no speed limit but is a bit of a slug at slow speeds, or a bike that is light and nimble but gets scary when going fast? Truth be told, it fully depends. It depends on a lot of things – your ability level, your local trails, and simply what you prefer. When I first hopped aboard the Rocky Mountain Slayer 29, the most immediate thing I noticed was the sheer size of the bike. It’s simply massive. 29-inch wheels, 170mm of rear travel courtesy of a coil shock, a 63-degree head angle and one of the longest wheelbases I’ve ever ridden make this a formidable machine to swing a leg over. Rocky Mountain bills it as a freeride bike, and it most certainly is, but after riding it on all kinds of terrain for the past two months, what surprised me the most was the bike’s versatility. Yeah, I know it’s a cliché to say that in a bike review; but hear me out. It’s not a DH bike, but also not an XC bike or even a trail bike, and it never will be, but the truth is that the Slayer is capable of a whole lot more than you might think.

From the get-go, it was obvious the Slayer would descend like a bat out of hell – and more on how good the bike handles gravity later – but what truly got me interested was how effective it is a big-mountain adventure bike. I live in the Tetons, and with COVID-19 making shuttling and even bike park laps a little untenable, finding big long adventure rides in the mountains became a bit of a habit this summer. My riding partners and I would look at the map and find ways to piece together 3000-foot descents way out in the woods, seeing how long we could spend in the saddle at once. Notable local rides were in the Big Hole mountains of Idaho, on the Continental Divide near Big Sky, and pedaling laps on our home trails of Teton Pass. The bike also joined me on a socially-distanced road trip through the Pacific Northwest where I got the directly compare it to both another enduro bike and a downhill bike. In the end, the Slayer became my go-to bike for the type of riding I like to do most: using my own power to get to the top of really long technical descents.

The Tech

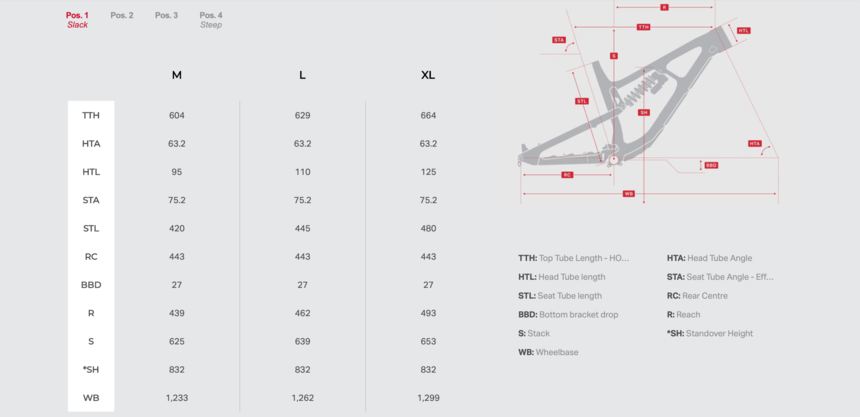

Rocky Mountain has been making the Slayer since 2001 and the current version (it came on the market late last year) is the seventh iteration of the design. Check here for our thoughts on the previous Slayer. It’s always been an aggressive bike, but never really fully slotted into one “category,” whether that was all-mountain, enduro, or even downhill. The new Slayer is the first to run 29-inch wheels, though a 27.5-inch version is also available that features a slightly different frame to accommodate the smaller wheels. The frame’s front triangle is carbon, with an alloy rear triangle, and features Rocky Mountain’s Ride-4 geometry adjust system that allows the rider to play with geometry angles. It adjusts the head angle from a ludicrously slack 63.2 to a more conservative 64.8 degrees, with two other options in between.

Click here for full geo numbers. On a fun note, the frame is designed to be compatible with 200mm dual-crown forks, and we’ve seen a handful of pros set up their bikes in this way.

Geo numbers in the slackest setting - why would you not run these on a bike like this? Rocky Mountain image.

Geo numbers in the slackest setting - why would you not run these on a bike like this? Rocky Mountain image.

I tested the 29-inch C90 version in size L, complete with some of the nicest and most appropriate components on the market. The stock C90 build comes with a 170mm Fox Float 36 fork, a coil-sprung Fox DHX2 shock, a Fox Transfer dropper post, alloy Race Face ARC 30 wheels with Maxxis double-down tires front and back, carbon Race Face SixC handlebars and Next R cranks, a Shimano XTR 12-speed drivetrain, and Shimano XTR Trail 4-piston brakes.

The C90 comes dripping in high-end gravity friendly components. Max Ritter photo.

The C90 comes dripping in high-end gravity friendly components. Max Ritter photo.

I ended up swapping the Fox Float 36 to a

180mm RockShox Zeb Ultimate to further beef up the bike. Necessary? Probably not, but with a bike like this, it seemed to make sense. Almost all the factory components are a smart spec, with super-plush suspension, extremely powerful brakes, a wide-range drivetrain, and lightweight components where they matter most. Carbon wheels are tempting on any bike, but the Race Face ARC 30 wheels have held up nicely, are pleasantly compliant, and super-stiff carbon wheels would likely take away from the comfortable ride – plus carbon rims are an expensive hobby when it comes to gravity riding. My only gripes with the frame are the press-fit bottom bracket, which tends to creak when it gets dusty, and the specialized rear shock hardware, which makes swapping the coil difficult.

Gravity Riding

So yeah, the Slayer descends really well. That shouldn’t be a surprise given its geometry numbers, component spec, and Rocky Mountain’s expertise in the freeride world. From looks alone, it looks like a single-crown downhill bike with a 12-speed drivetrain, and in some ways, that’s certainly true. However, let’s talk about some of the nuances on how it actually rides in the gravity realm, because that’s where it gets interesting. The Slayer has this sort of “sweet spot” of rider position you can hang out in and it will do just about anything you want it to. That sweet spot is much larger than on other bikes I’ve ridden, which kind of surprised me at first, and it translates to larger, more pronounced rider inputs being necessary to get the bike to turn, jump, or adjust a line. At first, it led to the bike feeling a little slow to respond, but in all honesty, I realized it just makes all other bikes I’ve ridden feel really twitchy. When you are going faster than you ever have on a mountain bike, stability, traction and a little bit of “sluggishness” are actually really nice – the bike doesn’t even feel like it’s going fast, so you just want to stay off the brakes even longer and let gravity hold on for just a bit more.

Gapping rocks on chunky trails? No problem. Katie Lozancich photo.

Gapping rocks on chunky trails? No problem. Katie Lozancich photo.

In the words of a friend who hopped aboard the bike for a few laps, “riding the Slayer is like being in a car chase with that crazy guy in the passenger seat telling you to run red lights, put the pedal to the metal, and completely ignore all the rules of the road – because you know you’ll get away with it.” In other words, don’t worry too much about line choice – just go fast and the Slayer’s got your back, you’ll be surprised of what this bike will let you do.

Sign Up for the TGR Gravity Check Newsletter Now

The one caveat to all that stability and go-fast-ness is it comes at a price in really steep, windy terrain. The only time the bike did not excel while descending was on puckeringly steep Bellingham-style gnar where slow-speed precision and the ability to change direction on a dime was necessary. The bike’s sheer length combined with the 29-inch rear wheel made it difficult to maneuver through really technical terrain like that found on some trails in the PNW. Sure, it’s possible, but it would take a better rider than me to make it work.

Adventure Riding

We know the Slayer descends well. Instead of dedicating this portion of the review to “does it climb well,” let’s talk about a more real-world scenario. There’s better bikes out there if you’re looking to hunt uphill Strava times. But, back to those huge gnarly descents that are nowhere near a shuttle road or chairlift – the Slayer might just be the perfect bike for that type of riding.

It’s quite comfortable to pedal for long distances thanks to a relatively relaxed seated climbing position. On technical uphill bits, the bike is surprisingly nimble, and let’s not forget that 29-inch wheels are much more adept at simply rolling over stuff. Additionally, the DHX2 coil provides that same unparalleled traction on the climbs, meaning you can sit and spin over loose rocks, chunky roots, and other non-grippy surfaces and make it up. I found myself using the lockout switch frequently to prevent pedal bob, particular on fire road climbs, but that’s a happy tradeoff for how well that shock performs otherwise. Finally, the 32-tooth front chainring combined with a 51-tooth cog out back gives you the granniest of granny gears. On those long adventure missions, I found myself hike-a-biking far less than I feel like I would have on another bike, surprising myself nearly every time I went out with what I was making it up without dabbing. Even with the super-slack head angle, it’s easy to maneuver up and over relentless roots and ledges, around tight uphill switchbacks, and responds to out-of-the-saddle sprinting. Unlike many other bikes with such geo numbers, I rarely found the front wheel wandering.

Of course, the best part of having a bike like this that can hang on long rides is pointing it downhill. High speeds, railing berms, and hitting jumps on shuttle trails and the bike park are one thing, but it’s rare you’ll find those on a backcountry ride. There, it’s often about slow-speed tech and careful line choice. The Slayer has a pretty simple answer to that: don’t worry too much about line choice or carefully picking your way down stuff. The monster-truck wheels and suspension combined with the head angle will let you get creative in that department, no matter what the speed. “Is this really a good idea?” turned into “let’s find out.”

The best of having a bike like this that can pedal up just about anything is how fun it will be on the way back down. Katie Lozancich photo.

The best of having a bike like this that can pedal up just about anything is how fun it will be on the way back down. Katie Lozancich photo.

The Final Verdict

Many of us probably don’t live in areas where massive human-powered descents are a thing. The Slayer probably isn’t the best bike for you then. However, if you live in a place with some rowdy riding and you’re looking for one bike to do it all, especially if “all” means “all the descending,” the Slayer can hang. It’s a phenomenal bike park bike, it’s a race-winning enduro bike, it’s a more-than-capable big-mountain adventure bike. Really, it’s a

mountain bike in the truest sense of the word that allows you to play with gravity unlike any other machine I’ve ridden.