Results 1 to 1 of 1

Thread: The Blues (Mountains, that is)

-

06-16-2019, 11:21 AM #1

The Blues (Mountains, that is)

Looks like a neat book:

New book explains why they call them the Blue Mountains

They are not the tallest mountains in the West, nor probably the prettiest, but for many people living in northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington, the Blue Mountains are cherished as a close-to-home escape from the modern world.

To some they may seem plain, as mountains go. They lack towering peaks, permanent snowfields and cirque lakes. But those who have taken the time to explore the Blues, from their high points to the deep canyons, know they are a secret stash of wild country with a great diversity of plants, animals and topography.

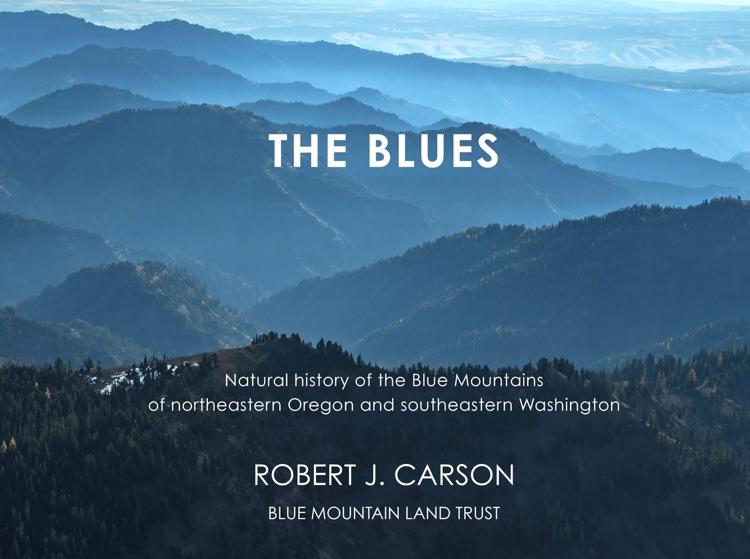

Bob Carson of Walla Walla captured the essence and mystique of the modest yet endearing mountain range in his new book “The Blues: Natural History of the Blue Mountains of Northeastern Oregon and Southeastern Washington.”

A retired professor of geology and environmental science at Whitman College in Walla Walla, Carson constructed his tome, the fourth he has written, as a mix of a classic coffee-table book with stunning photography and a natural history essay on the range he describes as roughly stretching southwest from Clarkston to Clarno, Ore.

“That was the goal: something for everybody,” he said. “My goal on these books is that there be something in there for professional geologists and there be something for the interested lay person.”

Published by Keokee Books of Sandpoint, the book serves as the fourth in a series, with the first three written by the Blue Mountains Land Trust. Carson had help from a host of photographers, with the bulk of heavy lifting by the late Duane Scroggins of Walla Walla and Bill Rodgers of Waitsburg.

In the book, he touches on the remarkable features of the Blues, including the interesting geology, streams and rivers, and forests and grasslands. He even explains why the mountains are a pleasing deep blue when viewed from afar.

“They look blue because of the scattering of sunlight in the atmosphere between the observer and the mountains,” he wrote. “The farther you travel from the mountains, the more air between you and them, and the more blue they appear.”

One of his favorite features is the mix of wet and dry soils that leaves some of the slopes covered with conifers and others blanketed with native grass and wildflowers.

“The north- and east-facing slopes have magnificent forests, and the south- and west-facing have grasslands and scattered pines. If the whole range were wetter, it would be all forest, and if the whole range were drier, it would all be prairie,” he said. “It’s really amazing and ideal for mammals and birds in terms of hiding from storms, hunters and predators in the forest and doing most of their foraging out in the meadows.”

The mountains weren’t high enough to be glaciated. So instead of U-shaped canyons carved by slow-moving ice, they’ve been eroded by tumbling and twisting streams and rivers, leaving them steep and V-shaped. The spongelike nature of the basalt bedrock absorbs some of the water during spring runoff, which later seeps back into streams, leaving them with plenty of water even during the scorching months of July and August.

The mountains, occupying a relatively unpopulated region, offer ample solitude for visitors, Carson writes:

“The Blues are sparsely populated. One can drive the roads for miles, seeing more deer than vehicles. A herd of elk may graze in a meadow on a ridge in the grass-tree mosaic. A black bear may be moving slowly along a slope, looking for food. A coyote may run, then turn back to look at the visitor. Unlike other mountain areas in the Pacific Northwest, rarely does one see others when hiking in the Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness.”

The book is available online at http://keokeebooks.com/ or in Walla Walla at the Blue Mountain Land Trust, Whitman College Book Store and Earthlight Books.“When you see something that is not right, not just, not fair, you have a moral obligation to say something. To do something." Rep. John Lewis

Kindness is a bridge between all people

Dunkin’ Donuts Worker Dances With Customer Who Has Autism

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks