Survival tips from the Blue Tambo. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

Survival tips from the Blue Tambo. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

Powdery photos of steep chutes in the Andes are being tossed around Instagram because Chile and Argentina are experiencing a great, snowy August. With a lot of these gorgeous shots of high alpine, knee-deep turns, athletes, writers, and photographers (and us) have posted various tips about how to travel to South America cheaply and what to expect.

I want to be honest here. I’ve been traveling throughout Chile this August on my own shred mission. Some of this content really misses the mark. Yes, bring a converter (actually one for every device you’re going to use). Use the great bus system, and expect them to be slow. Wait hours, if not days, for the precariously windy roads up the mountains to open. Anticipate everyone and everything to be later than they would be in North America. Bring all the gear you think you might need and then sell it because people here don’t have easy, affordable access to the rad gear you have. All that’s true.

The 10,000-peso ride from Santiago to Chillan. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

The 10,000-peso ride from Santiago to Chillan. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

But these are the cutesy tips that make for mild inconveniences during the present, and funny stories after they pass. If you’re really going to drop $1,000 to fly to Santiago or Buenos Aires (and you should), let’s lift the veil and drop the bullshit. Here are some real things you will experience after you get your passport stamped.

#1: There is no Chilean Avalanche Center with forecasters putting out regular updates about what’s going on in the snowpack

The Fingers at Nevados de Chillan. Look but do not touch. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

The Fingers at Nevados de Chillan. Look but do not touch. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

Love those deep powder shots? Me too. Want that to be part of your time in South America? Me too!

However, if you are going off-piste, get local information about the snowpack, preferably from ski patrol if you speak Spanish, and from certified, trained guides leading backcountry tours. Talk to people who have been riding inbounds and out and ask them what they’ve seen. Dig pits, assess, and then reassess the snowpack.

Take it a down a few notches with the understanding that all your information might not be reliable. Why? Because the Chilean government hasn’t created a national avalanche center. There’s no avalanche forecasting outside of the resorts.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Liz Daley, JP Auclair, and Andreas Fransson–three tremendously experienced, competent, ski and splitboard mountaineers who died in avalanches in Chile last fall.

Mostly, I have been wondering: if there were more widespread avalanche forecasting and discussions about what’s going with the snowpack in Chile, would these accidents have happened in the first place?

Maybe that’s unfair, but it brings up the point that you really are on your own down here. You can really know what you’re doing. You can strive to make the right decisions all the time. And horrible things can still happen. You are human. You can still make mistakes. And now you’re going into a place without a nationwide system for documenting changes in the snowpack.

#2: Wind dramatically affects the snowpack in the Andes

A front moving in. It's about to be a full-on white-out. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

A front moving in. It's about to be a full-on white-out. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

South America is a world class place to make turns in snow. Do not get me wrong. That’s not to be understated. Empty the bank account and come down here today.

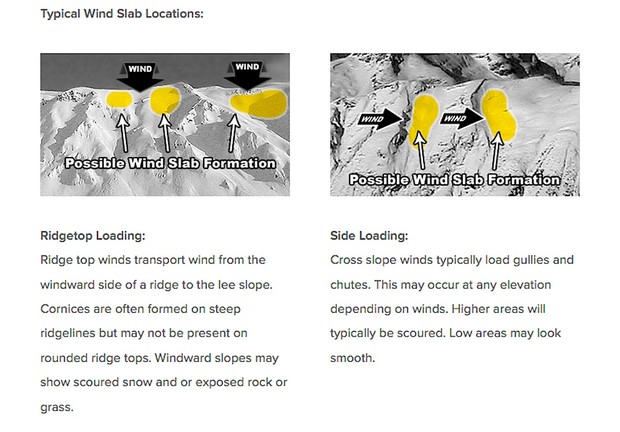

That said, wind events happen regularly. All of these factors, combined with challenging low visibility, can make it surprisingly difficult to spot what’s been toploaded versus crossloaded, and when. Know how to identify wind-loaded deposition areas versus eroded, stable areas and employ that knowledge whether you are inbounds or out-of-bounds.

Wind slab formations. FSAvalanche.org photo.

Wind slab formations. FSAvalanche.org photo.

A quick anecdote: I wanted to hit a fairly mellow cliff drop on a north-facing slope of mostly eroded, semi-soft snow, and motioned to one of my crew to scope the landing. He motioned back to me to wait as he ski-cut the west-facing ridgeline to my left. A good, normal call because the likelihood of wind-deposited snow was high near the landing and the runout. As he cut the slope, a waist-deep wind slab slid about 25 meters in what could have been my runout.

A closed "Freeride Area" at Nevados de Chillan. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

A closed "Freeride Area" at Nevados de Chillan. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

Here’s the kicker: we were inbounds in a controlled area at a reputable resort with a ski patrol that bombs, ski-cuts, and regularly closes areas that might slide. We had avy equipment, anticipating something like this could happen–but what if we hadn’t? What if we were like the ten other people we saw dropping into the same area later that day after ski patrol closed it?

#3: Surface lifts are your friend. Embrace them now and avoid lift-closure resentment

My obnoxious T-bar selfie was quickly followed by a tomahawk. Instant karma? MacKenzie Ryan photo.

My obnoxious T-bar selfie was quickly followed by a tomahawk. Instant karma? MacKenzie Ryan photo.

Per the wind and the low visibility situations, many a summit lift stays closed. Don’t fret. Remember your childhood learning how to ride and getting pulled up the slopes via T-bar? Your once-in-a-lifetime trip to South America to ride pow is the perfect time to employ that muscle memory.

T-bars and Poma lifts do tend to burn your legs up a bit. You also should definitely listen to the signs that read “No Hacer Zig-Zag,” because failure to do so will certainly result in an accidental 90 or 270-flat-spin to the ground. Whoops.

#4: Few buildings will be heated. Most buildings will not have insulation

A frosty, bluebird day at Nevados de Chillan. Most accommodations will not provide much relief. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

A frosty, bluebird day at Nevados de Chillan. Most accommodations will not provide much relief. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

One morning I pointed out how remarkably small and oxygen-deprived the wood stove was in our Las Trancas cabin near Nevados de Chillan. My friend remarked that I should expect this trip to be basically winter camping. I wish I had known to bring my zero-degree sleeping bag and JetBoil. These two pieces of gear would have made every hostel, house, cabin, and apartment I’ve stayed in substantially more comfortable in the evenings.

Most residences use wood to heat. This is no big deal if you can share fire-tending duties with all of the members of your travel party. Set a wake-up-and-add-wood schedule. If someone forgets to add logs to that fire, you will be waking up in the frigid cold to start a fire in a dinky wood stove before your morning coffee.

Ski lodges and most buildings at the base, including cafeterias, also will most likely not be heated at all.

#5: Pack your own coffee and French press

Whoever developed Nescafe should be put in jail. Not for a long time, but maybe for a month–just enough for them to rethink that recipe. It’s awful.

Instant coffee does represent a cost-effective alternative to real coffee for people who cannot afford it. We can all get behind that. However, Nescafe is easily the worst of all the instant coffees and certainly not the cheapest. Therefore, its popularity in Chile is inexplicable.

When you do find an actual coffee shop, treat yourself. Because, unless you packed coffee and a French press, the rest of your trip you will be drinking Nescafe with powdered milk. No bueno.

#6: Stray dogs roam the streets

There will be strays. Some cuter than others. Ryan Dunfee photo.

There will be strays. Some cuter than others. Ryan Dunfee photo.

A Santiago cab driver explained to me that people let their family dog’s puppies go free in the streets, creating packs of street dogs throughout the city.

Truthfully, most dog and cat owners don’t spay or neuter their animals. When these hard-working Chileans go to work, their pets go out and, let’s say, get frisky. The result is a large population of underfed, unwanted, homeless dogs who are almost entirely self-sufficient. Encountering street dogs is mostly an endearing experience. They do what they want: chase cars, lounge in the sun, and find people to give them a little extra food.

A Canadian skier I met told me that the dogs know which homes to go to get fed, and that they are beloved in certain neighborhoods. That seems to be the case for most of them. Inevitably one or two of every pack has gotten hit by a car and still runs around on three legs. Sometimes it’s powerful to see such a display of perseverance. Other times, a three-legged dog will be taking its last breathes in the parking lot of grocery store, and it’s heartbreaking.

You might be thinking, dying three-legged dogs? What about the rampant poverty and huge gap between rich and poor? Don’t worry. We’re going to get to that.

#7: A real Chilean ski experience means you actually experience Chilean people outside of ski resorts

A weaver outside of Curacatin. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

A weaver outside of Curacatin. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

The single most annoying thing I’ve experienced in the past two weeks is watching everyone post photos of Portillo or Bariloche on a powder day without a single discussion of the world around those places. Oh, wow, the best storm in five years? We’re presenting a fantasy by doing this.

Chains only and limited space in the truck means I am in the back of a pick-up for the ride up. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

Chains only and limited space in the truck means I am in the back of a pick-up for the ride up. MacKenzie Ryan photo.

Outside of those snow-covered wonderlands are areas (rural and urban) with incredible poverty, and people living a truly rugged mountain life.

Just like someone who never hiked up a mountain doesn’t have a practiced appreciation for chairlifts, you don’t appreciate a South America shred trip without recognizing you have what others do not. Corrugated roofs, horse-drawn carriages, and nearly collapsed, makeshift shelters aren’t uncommon sights. So it’s hard to complain about the road to Farellones requiring chains or the internet being slow.

Matt Clark | ClarkleberryFinn

August 19th, 2015

“Whoever developed Nescafe should be put in jail. Not for a long time, but maybe for a month–just enough for them to rethink that recipe. It’s awful.”

Haha so true! Great article btw!

el Reido

August 29th, 2015

Awesome!!