tags:

Niseko, Japan |

ugc |trip report picks |snowboard |ski |premium content |niseko japan powder |news |japan |featured |backcountry

Opening weekend at Grand Hirafu Resort, Niseko, Japan - photo courtesy Amy McDonald

As I sit typing this, I have just ripped the deepest powder of my life. I’m talking about opening weekend at Grand Hirafu Resort in Niseko. Waist deep. Short lift lines. Sunshine.

How could it get any better than this?

That’s the thought process behind the Hokkaido Backcountry Project, our Kickstarter that was successfully funded on Saturday.

Partnering with the Hokkaido Backcountry Club and Dragon Helicopter, we’re creating a documentary and web series that follows the first modern helicopter ski and snowboard operation on the island of Hokkaido in northern Japan

But “better” doesn’t always mean more powder, bigger mountains, and helicopters or other toys to get there. Here in northern Japan, appearances are not always what they seem.

Dragon Heli pilot Inada-san lands on Shiribetsu-Dake.

In Hokkaido, off-piste skiing and snowboarding began as a resort option because so few Japanese people skied the trees in between runs. Guide services eventually popped up to take advantage. Legions of Australians, Kiwis, Americans, and Canadians showed up. Lodges run by foreigners came into existence.

Fast forward a few decades, and the popularity of Japan’s powder continues to pile up, while backcountry safety, public access, and government oversight lags behind.

We’re talking about confusing gate policies, a lack of standardized avalanche prediction, and palpable fear and uncertainty from government and private businesses when confronted by requests for access to the backcountry via snowcat, snowmobile, and helicopter.

The Hokkaido Backcountry Club and myself connected on TGR with the following goal: show how this helicopter operation can make the Hokkaido backcountry safer and more accessible.

You can read our original post in the TGR forums here.

While many have been supportive of this goal, others have taken odds with the project. HBC welcomes all feedback, both positive and negative. Here's a sampling of responses we've gotten from TGR members:

"I'm curious how the local (not industry douchebag/gaijin/people like us) touring community is responding to the heli op."

"Having skied with many Cat and Heli ski operations in Canada over the past 25 years I would rate the HBC heli guides from 2014 to be top notch."

"I hope you can cut through the Japanese red tape quickly and fly to mountains that are not so heavily used by BC tourers."

"You should be advised that the idea of a heli operation on limited terrain that has already been in use by locals is causing significant noise in the community."

Here's just one observation I've made so far:

Last week, I traveled to the rural community of Shakotan-cho with Dragon Heli operator Makoto Koizumi. This fishing village on the sea of Japan is surrounded by rugged cliffs and deep maritime powder. We met with 86-year-old Horiuchi-san, who financed Hokkaido’s first heli ski operation more than 30 years ago in the mountains above this small town.

Speaking a few words of English, the gentle octogenarian cracked a big smile, and emphasized skiing the “back bowls” of nearby Shakotan Mountain, or Shakotan-Dake in Japanese.

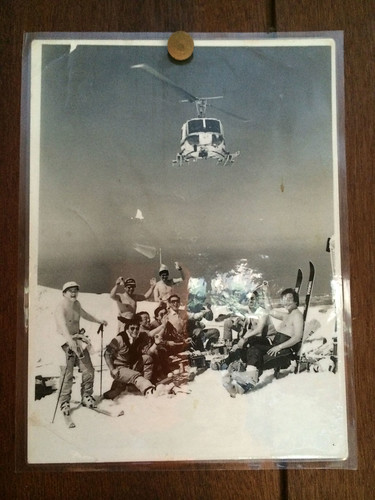

Original promo photo for the Shakotan heli operation

Sipping tiny coffees, Makoto and I chatted with the former businessman as his kerosene heater pumped and fat snowflakes melted on the nearby window. Horiuchi-san showed us maps and other documents detailing the heli and snowcat operation when it started in the mid 1980s.

Due to his failing health and a slowing economy, Horiuchi-san and his partner Gaman-san eventually closed the heli operation after 20 years in business. Horiuchi-san donated the land surrounding Shakotan-Dake to the municipal government of Hokkaido.

Tragically, four snowmobilers died in a massive avalanche a few years later. The date was March 19, 2007. More than 20 snowmobilers had taken part in a backcountry ride near the 4,117 foot peak when a cornice dropped and buried half the group. Military rescuers and local police worked for more than 24 hours to find the survivors and buried bodies. Nobody had avalanche gear.

Here’s a recap of the accident in the Japan Times

View from the fishing village of Shakotan-cho

In response, the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries banned motorized access in the area, citing safety concerns. When asked about risk management policy in the backcountry, an employee replied off the record “We hope people don’t go into the backcountry because it’s dangerous.”

The Hokkaido Backcountry Club and Dragon Helicopter hope to re-establish heli and cat operations in this community. Both groups want to do so with risk management tools that can help backcountry users avoid tragedies like these.

Basic practices like using avalanche beacons, probes, and shovels; using a standardized avalanche forecast system; and having emergency response plans are what’s needed.

The Black Diamond Crew gearing up for a hike at Annupuri Resort, December, 6 2014

While in Shakotan-cho, Makoto asked members of the local police and fire departments how they’d respond to a search and rescue emergency involving backcountry skiers or snowboarders in the nearby mountains.

Sitting in the police office, I watched as a concerned Japanese lieutenant suspiciously questioned Makoto. The response at the fire department was friendly, but just as dismissive. While these professionals were kind enough to speak with us, their responses were concerning.

Turns out, neither department has any formal search and rescue training or mountain rescue equipment. In fact, we learned the closest civil rescue service was likely more than two hours away in the city of Sapporo.

Left to right: Makoto Koizumi, Horiuchi-san and his wife, and Clayton Kernaghan meet for the first time

According to Hokkaido Backcountry Club owner Clayton Kernaghan, the popular saying Mitte-minai furi suru -- or “pretending not to see,” has been a popular response to these kind of questions for many years. It’s a saying shared by resort operators, the government, and skiers and snowboarders too.

“Recreational risk management has come a long way in Japan,” Clayton told me. “And we want to take it further.”

The Hokkaido Backcountry Project has been successfully funded on Kickstarter, and you can read more about it here.